Designing My Digital Knowledge Hub

Frameworks, Tools, and Reflections on Building a Second Brain

Six months ago, I wrote about “second brains,” an idea popularized by productivity expert Tiago Forte. At that time, I was upgrading my Notion-based second brain. Having made significant progress, it's time for an update.

I’ve been on a multi-year journey into productivity and have developed systems to help me manage my knowledge, priorities, and time. While I’m always working to improve them, these systems have effectively supported my progress on professional and personal projects.

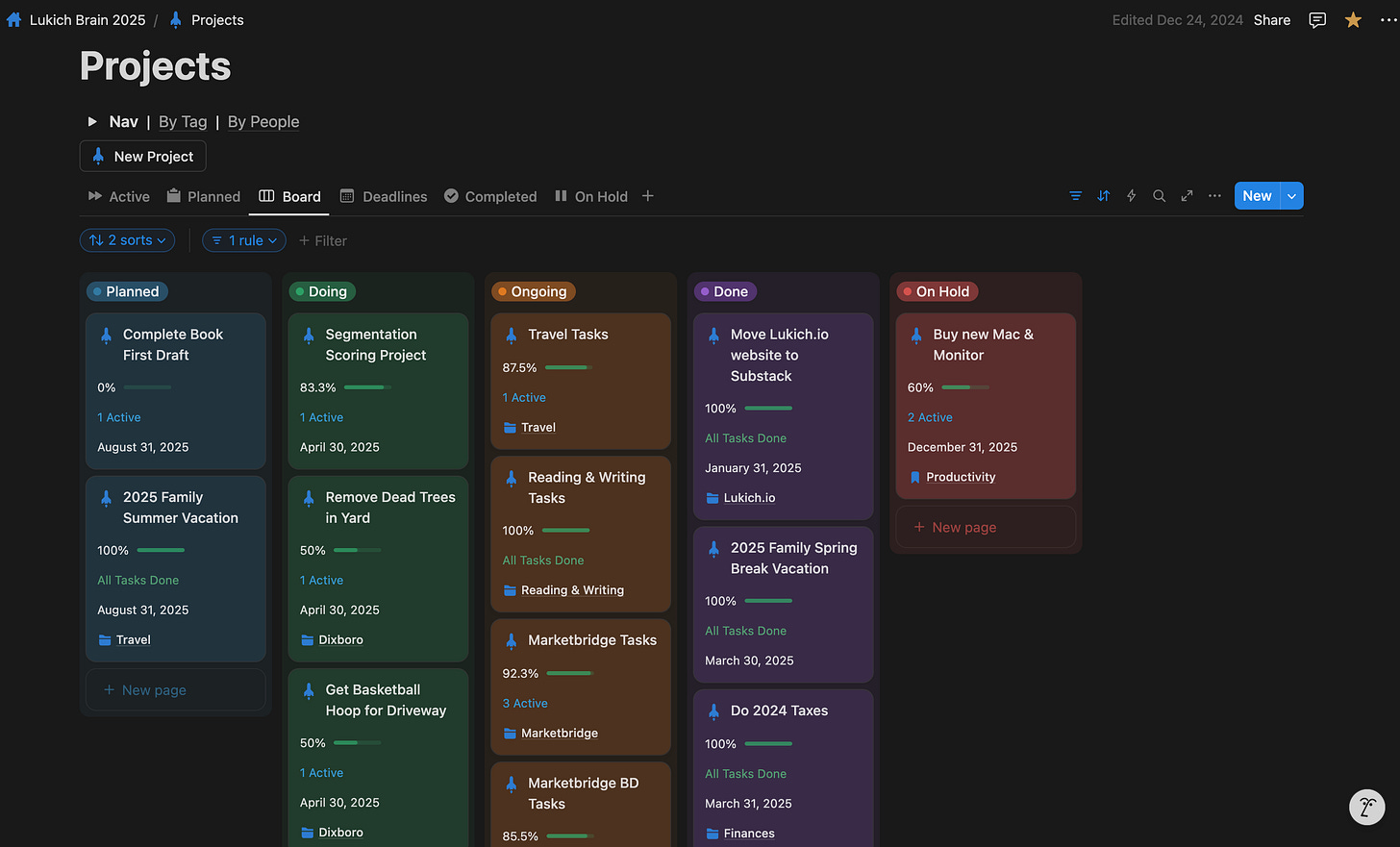

This essay focuses on the knowledge management component of my second brain system. I’ll share my framework and screenshots1 of different views within my workspace. If nothing else, they might inspire those embarking on their own productivity adventures.

An overview of Personal Knowledge Management

A “second brain” is an idea within the broader umbrella topic of personal knowledge management (PKM). PKM describes how you consume, store, and later use information. It also encompasses the tools you use to help you do so (software, physical storage, etc.).

While the field is relatively new2, PKM concepts have existed for far longer. Humans have been consuming and storing information since the beginning of time. It’s how we’ve cultivated and grown our knowledge as a species. Technology enhanced these abilities as we evolved from cave walls to paper to computers.

Regardless of the medium — digital notes on a laptop, a commonplace book, or a set of books on a shelf — humans have long understood the value of knowledge management systems. One of your greatest assets is what you know. It’s what makes you, you. Unfortunately, we all have a ceiling on how much we can remember. As a result, we’ve developed PKM systems to store additional knowledge outside of our brains. Like an external hard drive, a good PKM increases accessible information, which often leads to additional benefits, such as increased productivity or better performance.

In its simplest form, a PKM system can be pictured as a giant box made for storing knowledge.

In his Building a Second Brain book, Forte introduced the CODE framework to categorize the flow of information into, within, and out of this box. The four steps of the framework included:

Capture: The input of new information into the box.

Organize: The organization and storage of information within the box.

Distill: Enhancing the info within the box.

Express: Creation of new output based on the usage of information within the box.

I like this framework, but it’s missing one piece: the ability to easily find and gather information from the box. So, I’m adding a fifth part: Retrieve.

That leaves us with a new acronym: CODER. Let’s explore these phases and their role in a second brain system.

Capture

The Capture phase covers the process of putting information into the PKM.

Anytime we consume new information, we have a simple decision to make: Should we put this information into our PKM system?

If your PKM is physical, like a commonplace book, the answer might not be simple. There are space limitations, and it’s time-consuming, so you must be more selective about what you want to gather.

But if your PKM is digital, these constraints are removed. Storage is cheap, and you can automate much of what you gather. You can technically capture virtually everything.

Side note: just because you can capture everything, doesn’t mean you should. But that’s a topic for another essay.

Here’s a non-exhaustive list of what I include in my system:

Notes (from meetings, ideas, journal entries, plans, etc.)

Voice recordings to myself (usually dictated to myself while walking or driving)

Physical notes (I like using paper notebooks and often upload photos of pages I want to keep)

Web articles (I use a Chrome extension to provide context with additional notes when saving)

Podcast episode transcripts (I use a podcast app that uses AI to summarize key insights)

YouTube clips and transcripts (I use a Chrome extension to take additional notes when watching)

A common Capture pitfall is obsessing over immediate organization. There’s a simple solution: worry about organizing later.

I highly recommend separating the capturing and organizing. Forte agrees:

“The moment you first capture an idea is the worst time to decide what it relates to. First, because you’ve just encountered it and haven’t had any time to ponder its ultimate purpose, but more importantly, forcing yourself to make decisions every time you capture something adds a lot of friction to the process.”

Deferring organization feels counterintuitive; the urge to file something immediately is natural. But immediate filing often requires extra thought, especially for something that doesn’t fit nicely within a current project. Good PKM should be frictionless. To align with this principle, capture uncertain items in an inbox and organize them later.

While some form of manual capture will always exist, an increasing number of tools can automate the intake of podcasts, YouTube transcripts, and web pages. With minimal configuration, it’s easy to save this type of information directly into productivity software like Notion or Obsidian.

Organize

The Organize phase is a critical step in the process, happening within the PKM:

Good organization is about ensuring you can find what you need. After all, what’s the point of storing anything if you can't find it later?

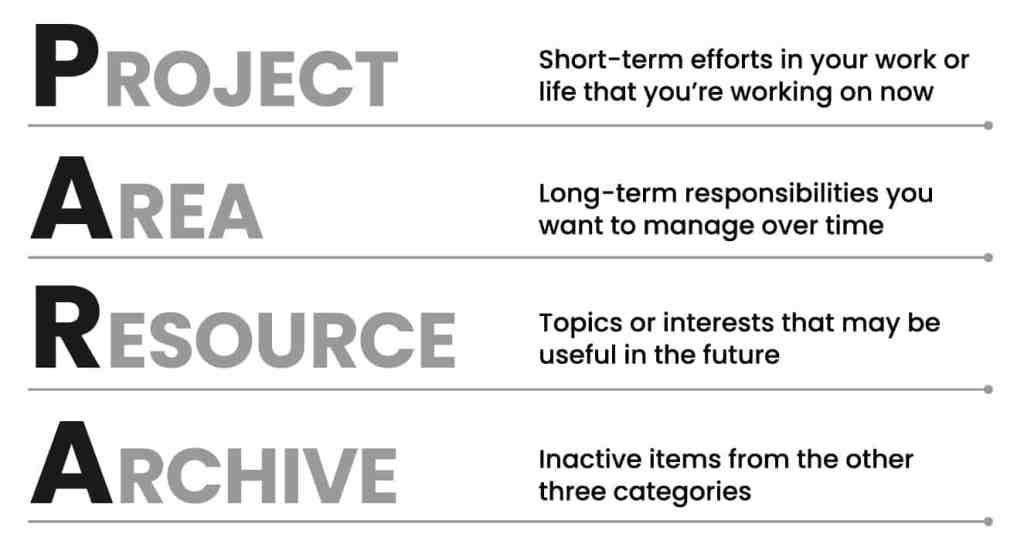

I use Forte's recommended PARA framework (Projects, Areas, Resources, Archive), where each represents one of your four parent folders.

When determining where to store a piece of information:

Check to see if it’s relevant to a project you’re working on or are about to work on.

If so, tag it or put it in a relevant Projects folder in your system. If no such folder exists, create one.

If it doesn’t align with a Project, move to the Areas folder and check to see if the information is relevant to an area of your life (e.g., family, work, hobbies).

If so, tag it or put it in a relevant Areas folder in your system. If no such folder exists, create one.

If it doesn’t align with an Area, tag it or put it in a relevant Resources (general topics and interests) folder in your system. If no such folder exists, create one.

If you’re initially organizing newly captured information, I assume you won’t pass the Resources folder and move on to Archive, which is more frequently used for post-hoc organization. For example, when the work on a project finishes and I no longer regularly need that particular information, I can move the project folder from Projects to Archive. If I need it later.

I started using this in 2022 and can attest to its usefulness. I find it reduces clutter and improves access to active information. I apply this framework across my digital footprint — my Notion 2nd Brain, work laptop folders, personal cloud folders, browser bookmarks, and more. Consistent naming and folder structure make finding context-specific information easy and fast.

I don’t think it matters what system you choose. It only matters that you have some organizational system; as long as you can find what you need, you can do anything that fits your unique life circumstances.

I would recommend that you devote regular time to organization. Neglecting this step leads to inbox clutter, overwhelm, and time-consuming catch-up. In addition, delaying organization risks forgetting the information's purpose.

I prioritize organizing during my weekly review. Because I don’t skip this process, cleaning my inboxes usually takes less than 5 minutes. Nothing builds up, and all information gets filed away for later use.

From time to time, you may want to update where a piece of information is stored based on different connections you identify. Or perhaps you want to tag additional Projects or Areas to reflect something else you want to associate with it. This is good and can make your storage system more robust. Both of these steps are easily done with most modern software tools.

Distill

The next step is the Distill phase, which happens within the PKM.

The Distill phase is about finding the essence of each piece of information that you take in. It’s about enhancing notes with your interpretation of the content, layering in independent thinking. It’s about making something your own.

I increasingly value this stage; embracing it unlocks potential, yet it's often neglected.

Have you ever returned to old notes, unable to decipher your own thoughts and ideas? The Distill phase is meant to prevent this. Instead of letting our raw notes stand independently, we can take a little extra time to summarize what they contain so that we remember the main point if we return to them later.

There are several ways to do this. Forte recommends bolding or highlighting key lines within a note. You can also summarize key points at the top of your notes with your thoughts or additional context.

I don’t try to distill everything. Most of the time, I leave my notes untouched. But for the important and/or dense notes, I recommend taking the extra time for this step. It can save you a lot of time later to have a short summary of a long transcript or action items and learnings at the top of a lengthy set of meeting notes.

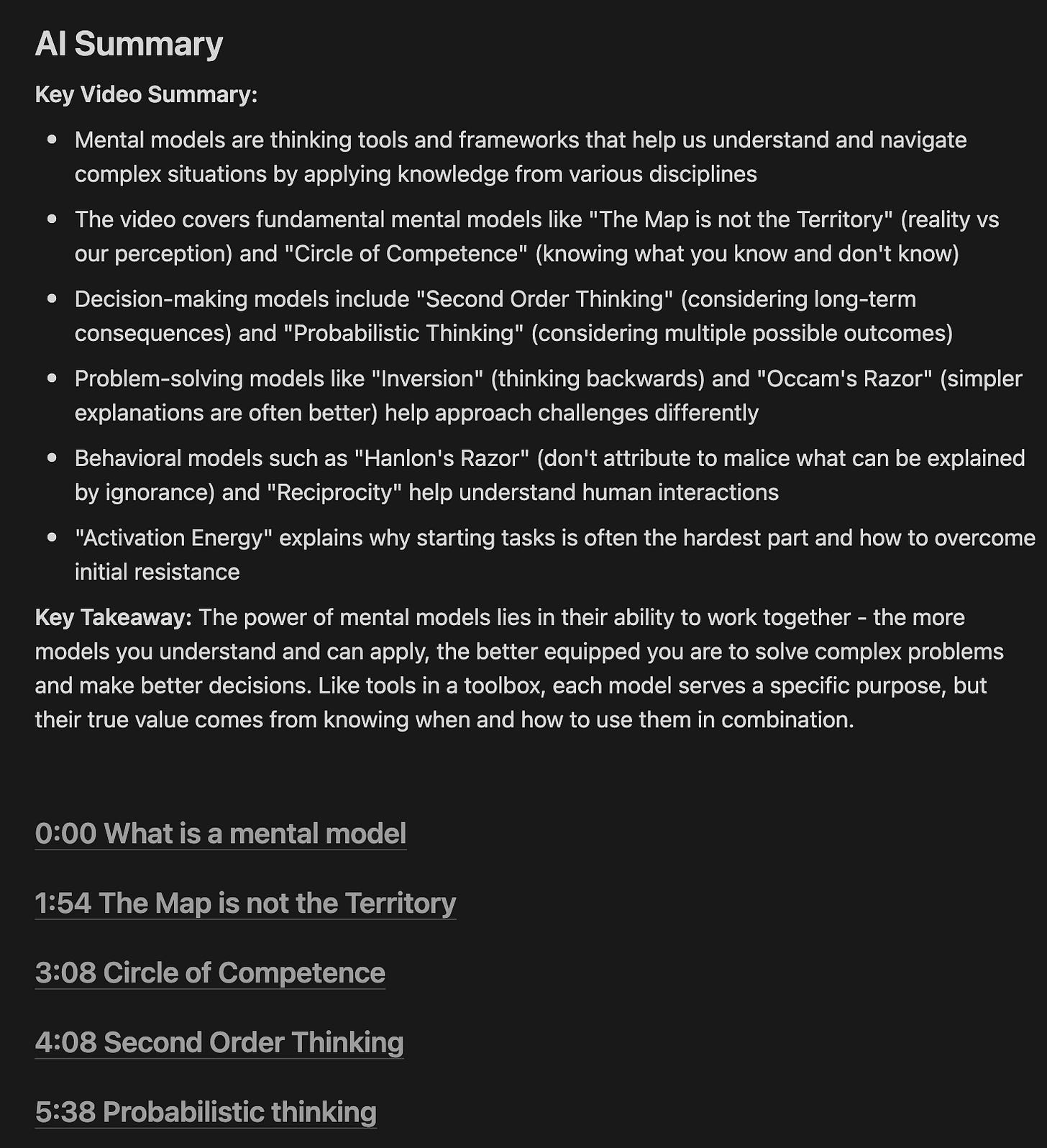

AI excels in this use case. The screenshot below shows a summary and takeaway generated by the LLM using the video transcript and a simple prompt. Alongside the notes I take from watching this video, I can be confident that I capture everything I need to understand, alongside my own insights.

Express

The Express phase is when you do your work.

In most cases, people work outside of their PKM systems.

With modern productivity tools like Notion, we can increasingly work within our PKMs. So I’ll describe the Express step here instead of at the end after Retrieve. That would have additionally required us to use the more clunky CODRE acronym, which doesn’t look as nice.

Working within your PKM has benefits. For one, it lowers friction (see the pattern). By working within the same place where you store your knowledge, you make it much easier to find and make connections. Creativity involves combining diverse knowledge to create something new; a well-organized PKM facilitates this.

AI excels here, too. Frontier LLMs (ChatGPT, Gemini, Claude) synthesize large amounts of text and find connections well. Exciting applications like NotebookLM allow you to upload source documents and videos and interact with them using an LLM.

Notion AI promises to bring everything together, but the model implementation isn’t quite there yet. I’ve found that it’s great when working with the text on a single page. But when I try to prompt it to bring multiple pages together or find pages that fit certain characteristics, it is inconsistent. As this use case continues to develop and better solutions are offered to the public, I believe there will be a significant step forward in the realm of personal creativity.

Retrieve

Retrieve, the final phase, is the outward flow of information from the PKM.

We typically retrieve information in several ways:

We know exactly what we want. We want to be able to access the information quickly. All that matters is our naming convention and/or organizational structure.

We know where to focus our search, but don’t know what file(s) we seek. Organizational structure is the most important factor. Good metadata tagging can help us use filters to search amongst a broad set of files.

We don’t know where to focus our search. Search is the most important factor. We can utilize built-in search or LLMs to broadly search lots of files.

Effective retrieval relies on good organization and search capabilities. When you organize, try to develop some consistency in a naming convention.

If your tool allows it, you can easily build custom views to surface things. The ability to sort by tags and other metadata lets you layer lots of context onto your knowledge so it can be part of many different searches. For instance, tagging notes by project allows custom views to consolidate them automatically, pre-retrieving needed info.

This framework also works physically, exemplified by Robert Greene's and Ryan Holiday's notecard systems for book writing. Greene and Holiday fill their books with ideas from the many books they have read. When they read something useful, they write a note on a notecard (capture) and store it in a card catalog (organize). They don’t copy everything from the book — they’ll summarize the idea and add their thoughts (distill). When it’s time for them to write their book, they’ll pull the notecards together (retrieve) and arrange them in a way that can be tied into a cohesive book (express) — the whole process in physical form.

Since starting down the PKM path 15 years ago, I’ve continually evolved my system. I think that’s normal and mirrors much of life. As the world evolves, so do the tools we have to help us improve our lives. I’m sure I’ll return to this in six more months with new perspectives to share.

A sound knowledge management system is critical to a calm mind. Without one, we’d be lost in this flood of information. We’d have to rely mostly on our brains, which is dangerous. We forget things. Memories change in our brains over time. It’s ok to turn to tools for help. Storing wisdom externally acts like a backup, easing the burden of remembering everything.

The people who can consume and best use this information will have an advantage over the rest. The key is finding a system that works for you, allowing you to seamlessly capture and use what you learn.

Thanks for reading. I’ll be back with another essay next month.

Until then,

Mike

I used Thomas Frank’s excellent Second Brain template as a foundation for my workspace. I have adapted the individual pages, databases, and views to fit my needs.

Frand, Jason; Hixon, Carol (1999), "Personal Knowledge Management : Who, What, Why, When, Where, How?", Working Paper, UCLA Anderson School of Management, archived from the original on 16 May 2007, retrieved 17 February 2008