Our Thinking Crisis

The Widening Gap Between a Complex World and Our Ability to Handle It

Last week, I shared the initial Table of Contents for my upcoming book, The Journey to Phronesis. Today, we take the first step on that journey by exploring the problem at the heart of the book and the topic of Chapter 1: our modern thinking crisis."

Our Thinking Crisis

I believe that one of the primary issues of our time can be described with two visuals.

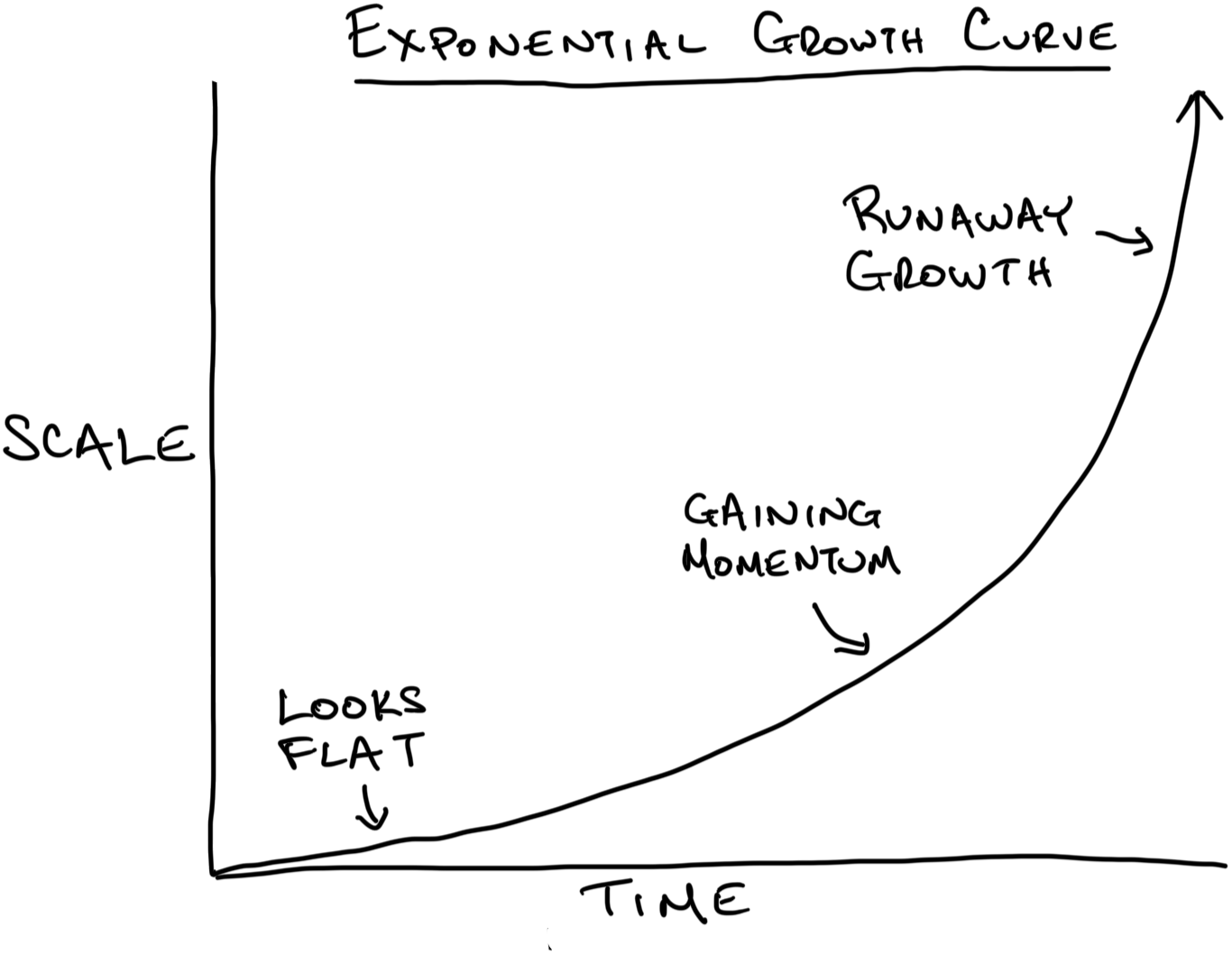

The first represents the increasing complexity of our world. It seems that everywhere we look, we see the unmistakable J-curve of an exponential growth curve displayed below. It’s challenging to pinpoint exactly where we stand on the curve, but it seems clear that the complexity of the world has been growing and continues to do so at an increasing rate.

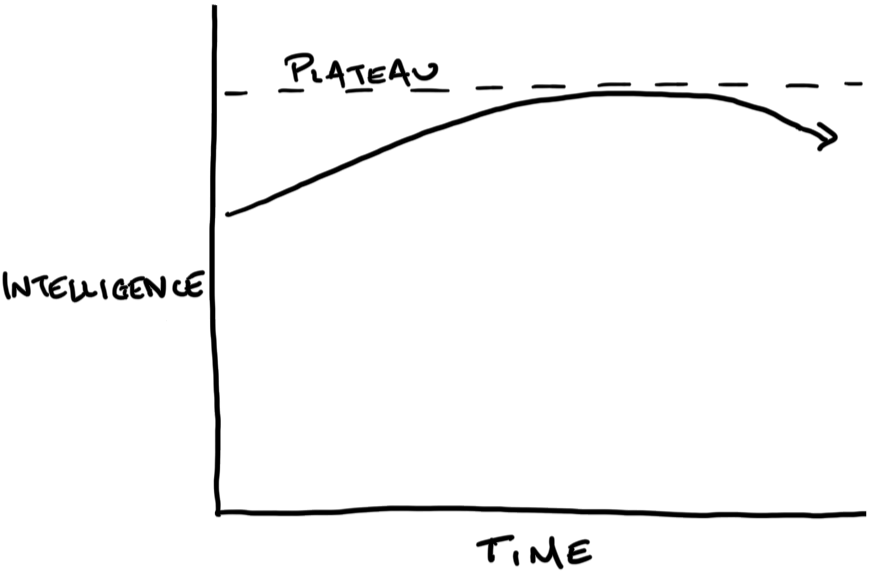

This increase in complexity is not a new issue. If we traveled back in time to any period of growth and change, we’d find the same problem. But this brings us to the second part of the equation. Our intelligence as a species has peaked and is now starting to decline, as represented by the illustrative graph below.

I think of the space growing between these two divergent curves as our “Thinking Gap.” And I believe it’s one of the defining, yet often unexamined, challenges of the 21st century. This gap is dangerously compounded by our own built-in cognitive biases and our increasing tendency to outsource our thinking to technology. The result is a pervasive thinking crisis that affects our ability to solve the most important problems we face.

The Evidence of the Gap

This widening gap isn’t just a feeling: it’s a measurable reality. Despite the obvious lack of detail on the graphs above, there is convincing evidence that supports this idea. To understand this, we can examine the ideas behind these curves more closely.

The Explosion of Complexity

I wrote a whole post about exponential growth earlier this year if you’d like to learn more, but the gist of it is this: the world we inhabit is changing at an exponential rate. In 1969, NASA sent astronauts to the moon using computers with a tiny fraction of the power of the smartphone in your pocket. Think about how wild that is. Your phone has approximately one hundred thousand times more computing power than the machine that guided the Apollo 11 mission. This isn’t the result of gradual improvement; it’s a technological explosion that has compounded throughout our lives.

Exponential growth isn’t limited to technology. The interconnectedness of the world creates incredible complexity. The COVID-19 pandemic was a stark lesson in this. In January 2020, a handful of cases were being tracked by epidemiologists; within months, millions had been infected worldwide. The virus spread through our global networks, revealing just how tightly woven our societies, economies, and supply chains have become.

These are only two windows into the power of this phenomenon. However, they are everywhere. We see it in economics, social networks, biology, and information transfer, to name a few. It’s hard to find domains where its presence isn’t a factor. The world is fundamentally more complex and interconnected than ever before, and exponential growth is how it manifests.

The Erosion of Our Thinking

This accelerating complexity would be manageable if our ability to handle it were also growing. But the evidence shows the opposite. Our thinking ability appears to be becoming less sharp.

Over time, human intelligence has increased. On the surface, this seems obvious. After all, we stand on the shoulders of giants, having become more capable beings. We’ve captured, organized, and synthesized the cumulative knowledge of many brilliant individuals who walked the Earth before us, helping us grow smarter. Several studies have supported this idea, with one of the most notable being the Flynn Effect. Observed by James Robert Flynn, this effect is the long-term increase in intelligence throughout the 20th century as measured by test scores.

However, we’ve recently seen evidence that our intelligence may have plateaued or even started to decrease, creating what is referred to as the Reverse Flynn Effect. While there are still many incredibly brilliant individuals, the aggregate trend looks grim. Standardized test scores indicate a decline in analytical skills. Academic studies suggest that critical thinking has been declining over time. Surveys reveal that most people, including educators themselves, cannot even define the thinking skills we desperately need.

The picture is clear. As the world’s problems become increasingly complex, our ability to think through them is deteriorating.

Identifying the Culprits

Our world is becoming increasingly complex, and our thinking skills are in decline. What’s causing this divergence? Unfortunately, the answer isn’t a single cause. Few answers to big problems are in life. Instead, it’s a set of powerful, interconnected forces. While there are numerous factors we could explore, I’d like to zoom in on three main culprits.

Our Brains: The Deck is Stacked Against Us

Unfortunately, our first challenge is one that is baked into our evolution. Our brains, for all their marvel, are not designed for objective truth-seeking; they are survival machines loaded with cognitive biases that evolved for living in a much simpler world. As Daniel Kahneman explained in his groundbreaking book, Thinking Fast and Slow, we spend most of our time in “System 1” thinking — a fast, intuitive, and emotional mode. This way of thinking excels at recognizing simple patterns but is a liability when facing complex, interconnected problems that require the slow, deliberate, and logical work of the “System 2” part of our brains1.

Our Schools: An Outdated Educational System

Second, our educational institutions are not filling the gap, and in many ways, they are compounding the problem. The Educational Testing Service conducted a 2015 study of college students and found that only 4% were proficient in critical thinking. Another way of reading that is that 96% of students cannot demonstrate proficiency in the most essential skill for modern life. We’ve created a system that often produces students who can memorize facts but cannot analyze, synthesize, or evaluate them. Students often come to believe that success means regurgitating the single correct answer rather than critically questioning the premise. We are producing compliant test-takers when what we actually need are adaptive thinkers.

Our Tools: The Price of Outsourcing Our Skills

Finally, we are weakening our mental muscles by outsourcing our cognitive work to technology. To develop and maintain any skill, practice is essential. I played the guitar for a few years in my 20s. Because I practiced, I got better. But I stopped practicing 15 years ago, and as a result, I can’t play nearly as well when I occasionally pick up the instrument. Thinking is no different. It’s a skill like anything else. And we’re no longer practicing it. We used to have to think to get through everyday life. However, as technology becomes increasingly ubiquitous in every aspect of our lives, we’re outsourcing more of our cognitive work. Algorithms decide what we see, GPS tells us where to go, and AI answers our questions. Technology is incredible, and many of these tools can enhance our lives considerably. Yet by overrelying on them, we’re atrophying our ability to think for ourselves. While the first two problems are systemic and uphill battles to fight, this third one is of our own making. We’re willingly giving away the thing that makes us human. To me, that’s the most concerning one.

The Path Forward

Complexity won’t stop increasing — the ship has sailed on that one. But we can turn the decreasing trend in our thinking around. We can improve this uniquely human skill by actively practicing and refining our cognitive abilities. One of the most effective approaches I know to help people become better thinkers is to practice the concepts of systems thinking.

Systems thinking is an approach that equips us with the language and tools to see the interconnections, feedback loops, and unintended consequences that exist within the world. Leading global organizations consistently validate its value as a critical competency for the modern world. The World Economic Forum’s Future of Jobs Report 2023, for instance, lists systems thinking as a core skill necessary for success in today’s workplace.

The ability to understand dynamic interconnected systems is not a niche skill limited to business leaders, engineers, scientists, or other professionals. It is an invaluable tool for anyone looking to navigate life effectively. The Stoics and other ancient philosophers understood this. Many of the writings of Marcus Aurelius, Seneca, and Epictetus demonstrate that these thinkers intuitively grasped many of our modern systems concepts over 2,000 years ago. The Stoics used these ideas as practical tools to find clarity and purpose in their own chaotic world — the very skills we need to reclaim today.

Your Invitation to the Journey

This thinking crisis is the problem I set out to address in The Journey to Phronesis. While the book will officially be available in the spring, preorders open on Monday, October 6th. I have a set of unique and exciting packages to offer as a part of this fall campaign. I’ll share more details about how you can reserve your copy and support the book’s publication in the coming weeks.

Additionally, I have room for one or two more final beta readers to work through an early version of my manuscript. If you’re passionate about these ideas, can commit to reading the book in the next 4-6 weeks, and are willing to provide thoughtful feedback, please sign up at this link.

Conclusion & Next Week

The gap between the world’s complexity and our ability to handle it is real and growing more perilous. Yet hope is not lost. We can reverse this trend. We can choose to build better mental tools and reclaim the essential human skill of thinking. Recognizing the nature of the challenge we face is the first, crucial step toward solving it.

Now that I’ve defined the problem, it’s time to explore potential solutions. In next week’s post, I’ll provide a sneak peek into the rest of Part 1, in which I outline the foundational concepts of systems thinking and how they can be used for the problems of our lives.

I look forward to taking that next step with you.

All the best,

Mike

You can read more about System 1 and System 2 thinking in this excellent overview by the Decision Lab. I reference these ideas throughout the book.